See the Louisiana Purchase, from Wikipedia:

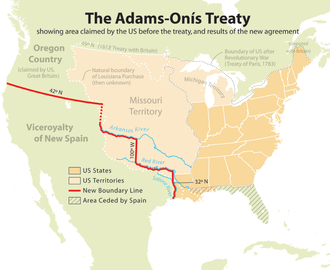

The Louisiana Purchase (1803) extended United States sovereignty across the Mississippi River, nearly doubling the nominal size of the country. The purchase included land from fifteen present U.S. states and two Canadian provinces, including the entirety of Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska; large portions of North Dakota and South Dakota; the area of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado east of the Continental Divide; the portion of Minnesota west of the Mississippi River; the northeastern section of New Mexico; northern portions of Texas; New Orleans and the portions of the present state of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River; and small portions of land within Alberta and Saskatchewan. At the time of the purchase, the territory of Louisiana's non-native population was around 60,000 inhabitants, of whom half were enslaved Africans. The western borders of the purchase were later settled by the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty with Spain, while the northern borders of the purchase were adjusted by the Treaty of 1818 with the British.

The Louisiana Purchase (1803) extended United States sovereignty across the Mississippi River, nearly doubling the nominal size of the country. The purchase included land from fifteen present U.S. states and two Canadian provinces, including the entirety of Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska; large portions of North Dakota and South Dakota; the area of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado east of the Continental Divide; the portion of Minnesota west of the Mississippi River; the northeastern section of New Mexico; northern portions of Texas; New Orleans and the portions of the present state of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River; and small portions of land within Alberta and Saskatchewan. At the time of the purchase, the territory of Louisiana's non-native population was around 60,000 inhabitants, of whom half were enslaved Africans. The western borders of the purchase were later settled by the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty with Spain, while the northern borders of the purchase were adjusted by the Treaty of 1818 with the British.

See The Missouri Compromise, from Wikipedia:

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state and declared a policy of prohibiting slavery in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36°30′ parallel. The 16th United States Congress passed the legislation on March 3, 1820, and President James Monroe signed it on March 6, 1820.

The Adams–Onís Treaty, from Wikipedia:

Negotiations between Spain and the United States continued, and Spain agreed to cede Florida. The determination of the western boundary of the United States proved more difficult. American expansionists favored setting the border at the Rio Grande, but Spain, intent on protecting its colony of Mexico from American encroachment, insisted on setting the boundary at the Sabine River. At Monroe's direction, Adams agreed to the Sabine River boundary, but he insisted that Spain cede its claims on Oregon Country. Adams was deeply interested in establishing American control over the Oregon Country, partly because he believed that control of that region would spur trade with Asia. The acquisition of Spanish claims to the Pacific Northwest also allowed the Monroe administration to pair the acquisition of Florida, which was chiefly sought by Southerners, with territorial gains favored primarily by those in the North. After extended negotiations, Spain and the United States agreed to the Adams–Onís Treaty, which was ratified in February 1821. Adams was deeply proud of the treaty, though he privately was concerned by the potential expansion of slavery into the newly acquired territories. In 1824, the Monroe administration would strengthen US claims to Oregon by ratifying the Russo-American Treaty of 1824, which established Russian Alaska's southern border at 54°40′ north.

1815-1880: Library of Congress

During this period, the small republic founded by George Washington's generation became the world's largest democracy. All adult, white males received the right to vote. With wider suffrage, politics became hotly contested. The period also saw the emergence--and demise--of a number of significant political parties, including the Democratic, the Whig, the American, the Free Soil, and the Republican Parties.

See The Plantation Era, From Wikipedia:

The Antebellum South era (from Latin: ante bellum, lit. 'before the war') was a period in the history of the Southern United States that extended from the conclusion of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. This era was marked by the prevalent practice of slavery and the associated societal norms it cultivated. Over the course of this period, Southern leaders underwent a transformation in their perspective on slavery. Initially regarded as an awkward and temporary institution, it gradually evolved into a defended concept, with proponents arguing for its positive merits, while simultaneously vehemently opposing the burgeoning abolitionist movement.

See Slave Power, from Wikipedia:

The Slave Power, or Slavocracy, referred to the perceived political power held by American slaveholders in the federal government of the United States during the Antebellum period. Antislavery campaigners charged that this small group of wealthy slaveholders had seized political control of their states and were trying to take over the federal government illegitimately to expand and protect slavery. The claim was later used by the Republican Party that formed in 1854–55 to oppose the expansion of slavery.

The term was popularized by antislavery writers including Frederick Douglass, John Gorham Palfrey, Josiah Quincy III, Horace Bushnell, James Shepherd Pike, and Horace Greeley. Politicians who emphasized the theme included John Quincy Adams, Henry Wilson and William Pitt Fessenden.

See the Second Great Awakening, from Wikipedia:

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a key part of the movement and attracted hundreds of converts to new Protestant denominations. The Methodist Church used circuit riders to reach people in frontier locations.

See Manifest Destiny, from Wikipedia:

"Manifest destiny" was a phrase that represented the belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("manifest") and certain ("destiny"). The belief was rooted in American exceptionalism and Romantic nationalism, implying the inevitable spread of the Republican form of governance. It was one of the earliest expressions of American imperialism in the United States of America.

See the Era of Good Feelings, from Wikipedia:

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Federalist Party and an end to the bitter partisan disputes between it and the dominant Democratic-Republican Party during the First Party System. President James Monroe strove to downplay partisan affiliation in making his nominations, with the ultimate goal of national unity and eliminating political parties altogether from national politics] The period is so closely associated with Monroe's presidency (1817–1825) and his administrative goals that his name and the era are virtually synonymous.

See John Quincy Adams, from Wikipedia:

John Quincy Adams (July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diplomatic and political career, Adams served as an ambassador and also as a member of the United States Congress representing Massachusetts in both chambers. He was the eldest son of John Adams, who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801, and First Lady Abigail Adams. Initially a Federalist like his father, he won election to the presidency as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, and later, in the mid-1830s, became affiliated with the Whig Party.

...Historians concur that Adams was one of the greatest diplomats and secretaries of state in American history; they typically rank him as an average president, as he had an ambitious agenda but could not get it passed by Congress. By contrast, historians also view Adams in a more positive light during his post-presidency because of his vehement stance against slavery, as well as his fight for the rights of women and Native Americans.

See the Jacksonian Era, from Wikipedia:

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21 and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson and his supporters, it became the nation's dominant political worldview for a generation. The term itself was in active use by the 1830s.

See Jacksonian Democracy in Brittanica:

... American politics became increasingly democratic during the 1820s and ’30s. Local and state offices that had earlier been appointive became elective. Suffrage was expanded as property and other restrictions on voting were reduced or abandoned in most states. The freehold requirement that had denied voting to all but holders of real estate was almost everywhere discarded before 1820, while the taxpaying qualification was also removed, if more slowly and gradually. In many states a printed ballot replaced the earlier system of voice voting, while the secret ballot also grew in favor. Whereas in 1800 only two states provided for the popular choice of presidential electors, by 1832 only South Carolina still left the decision to the legislature. Conventions of elected delegates increasingly replaced legislative or congressional caucuses as the agencies for making party nominations. By the latter change, a system for nominating candidates by self-appointed cliques meeting in secret was replaced by a system of open selection of candidates by democratically elected bodies.

These democratic changes were not engineered by Andrew Jackson and his followers, as was once believed. Most of them antedated the emergence of Jackson’s Democratic Party, and in New York, Mississippi, and other states some of the reforms were accomplished over the objections of the Jacksonians. There were men in all sections who feared the spread of political democracy, but by the 1830s few were willing to voice such misgivings publicly. Jacksonians effectively sought to fix the impression that they alone were champions of democracy, engaged in mortal struggle against aristocratic opponents. The accuracy of such propaganda varied according to local circumstances.

From These Truths pages 212-3:

If THOMAS JEFFERSON rode to the White House on the shoulders of slaves, Andrew Jackson rode to the White House in the arms of the people. By the people, Jackson meant the newly enfranchised workingman, the farmer and the factory worker, the reader of newspapers. In office, he pursued a policy of continental expansion, dismantled the national bank, and narrowly averted a constitutional crisis over the question of slavery. He also extended the powers of the presidency. “Though we live under the form of a republic,” Justice Joseph Story said, “we are in fact under the absolute rule of a single man.” Jackson vetoed laws passed by Congress (becoming the first president to assume this power). At one point, he dismissed his entire cabinet. “The man we have made our President has made himself our despot, and the Constitution now lies a heap of ruins at his feet,” declared a senator from Rhode Island, “When the way to his object lies through the Constitution, the Constitution has not the strength of a cobweb to restrain him from breaking through it.” His critics dubbed him “King Andrew.”

Jackson’s first campaign involved implementing the policy of Indian removal, forcibly moving native peoples east of the Mississippi River to lands to the west. This policy applied only to the South. There were Indian communities in the North—the Mashpees of Massachusetts, for instance—but their numbers were small. James Fennimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans (1826) was just one in a glut of romantic paeans to the “vanishing Indian,” the ghost of Indians past. “We hear the rustling of their footsteps, like that of the withered leaves of autumn, and they are gone forever,” wrote Justice Story in 1828. Jackson directed his policy of Indian removal at the much bigger communities of native peoples of the Southeast, the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Chocktaws, Creeks, and Seminoles who lived on homelands in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee, Jackson’s home state.

...

Jacksonians argued that, in the march of progress, the Cherokees had been left behind, “unimproved,” but the Cherokees were determined to call that bluff by demonstrating each of their “improvements.” In 1825, Cherokee property consisted of 22,000 cattle, 7,600 horses, 4,600 pigs, 2,500 sheep, 725 looms, 2,488 spinning wheels, 172 wagons, 10,000 plows, 31 grist mills, 10 sawmills, 62 blacksmith shops, 8 cotton gins, 18 schools, 18 ferries, and 1,500 slaves. The writer John Howard Payne, who lived with Cherokees in the 1820s, explained, “When the Georgian asks—shall savages infest our borders thus? The Cherokee answers him—‘Do we not read? Have we not schools? churches? Manufactures? Have we not laws? Letters? A constitution? And do you call us savages?”

They might have prevailed. They had the law of nations on their side. But then, in 1828, gold was discovered on Cherokee land, just fifty miles from New Echota, a discovery that doomed the Cherokee cause. When Jackson took office, in March 1829, he declared Indian removal one of his chief priorities and argued that the establishment of the Cherokee Nation violated Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution: “no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State” without that state’s approval.

...

The leaders of a tiny minority of Cherokees signed a treaty, ceding the land to Georgia and setting a deadline for removal at May 23, 1838. By the time the deadline came, only 2,000 Cherokees had left for the West; 16,000 more refused to leave their homes. U.S. Army General Winfield Scott, a fastidious career military man from Virginia known as “Old Fuss and Feathers,” arrived to force the matter. He begged the Cherokees to move voluntarily. “I am an old warrior, and have been present at many a scene of slaughter,” he said, “but spare me, I beseech you, the horror of witnessing the destruction of the Cherokees.” On the forced march 800 miles westward and, by Jefferson’s imagining, backward in time, one in four Cherokees died, of starvation, exposure, or exhaustion, on what came to be called the Trail of Tears. By the time it was over, the U.S. government had resettled 47,000 southeastern Indians to lands west of the Mississippi and acquired more than a hundred million acres of land to the east. In 1839, in Indian Territory, or what is now Oklahoma, the Cherokee men who'd signed the treaty were murdered by unknown assassins.“

The Nature of Progress from These Truths pages 191-2:

Tue United States was born as a republic and grew into a democracy, and, as it did, it split in two, unable to reconcile its system of government with the institution of slavery. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, democracy came to be celebrated; the right of a majority to govern became dogmatic; and the right to vote was extended to all white men, developments much derided by conservatives who warned that the rule of numbers would destroy the Republic. By the 1830s, the American experiment had produced the first large-scale popular democracy in the history of the world, a politics expressed in campaigns and parades, rallies and conventions, with a two-party system run by partisan newspapers and an electorate educated in a new system of publicly funded schools.

The great debates of the middle decades of the nineteenth century had to do with the soul and the machine. One debate merged religion and politics. What were the political consequences of the idea of the equality of souls? Could the soul of America be redeemed from the nation’s original sin, the Constitution’s sanctioning of slavery? Another debate merged politics and technology. Could the nation’s new democratic traditions survive in the age of the factory, the railroad, and the telegraph? If all events in time can be explained by earlier events in time, if history is a line, and not a circle, then the course of events—change over time—is governed by a set of laws, like the laws of physics, and driven by a force, like gravity. What is that force? Is change driven by God, by people, or by machines? Is progress the progress of Pilgrim’s Progress, John Bunyan’s 1678 allegory—the journey of a Christian from sin to salvation? Is progress the extension of suffrage, the spread of democracy? Or is progress invention, the invention of new machines?

A distinctively American idea of progress involved geography as destiny, picturing improvement as change not only over time but also over space. In 1824, Jefferson wrote that a traveler crossing the continent from west to east would be conducting a “survey, in time, of the progress of man from the infancy of creation to the present day,” since “in his progress he would meet the gradual shades of improving man.” His traveler—a surveyor, at once, of time and space —would begin with “the savages of the Rocky Mountains”: “These he would observe in the earliest stage of association living under no law but that of nature, subscribing and covering themselves with the flesh and skins of wild beasts.” Moving eastward, Jefferson's imaginary traveler would then stop “on our frontiers,” where he’d find savages “in the pastoral state, raising domestic animals to supply the defects of hunting.”"Next, farther east, he’d meet “our own semi-barbarous citizens, the pioneers of the advance of civilization.” Finally, he’d reach the seaport towns of the Atlantic, finding man in his “as yet, most improved. state”?

Maria Stewart's Christianity stipulated the spiritual equality of all souls, but Jefferson’s notion of progress was hierarchical. That hierarchy, in Jackson’s era, was the logic behind African colonization, and it was also the logic behind a federal government policy known as Indian removal: native peoples living east of the Mississippi were required to settle in lands to the west. A picture of progress as the stages from “barbarism” to “civilization’—stages that could be traced on a map of the American continent—competed with a picture of progress as an unending chain of machines.

See the California Gold Rush, from Wikipedia:

The California gold rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the United States and abroad. The sudden influx of gold into the money supply reinvigorated the American economy; the sudden population increase allowed California to go rapidly to statehood in the Compromise of 1850. The gold rush had severe effects on Native Californians and accelerated the Native American population's decline from disease, starvation, and the California genocide.