Excerpts from These Truths, pages 80-91:

Excerpts from These Truths, pages 80-91:

But the [Seven Years] war had left Britain nearly bankrupt. The fighting had nearly doubled Britain's debt, ... the king’s ministers determined that defending the empire’s new North American borders would require ten thousand troops or more, especially after a confederation of Indians led by an Ottawa chief named Pontiac captured British forts in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley.

Fearing the cost of suppressing more Indian uprisings, George III issued a proclamation decreeing that no colonists could settle west of the Appalachian Mountains, a line that many colonists had already crossed.

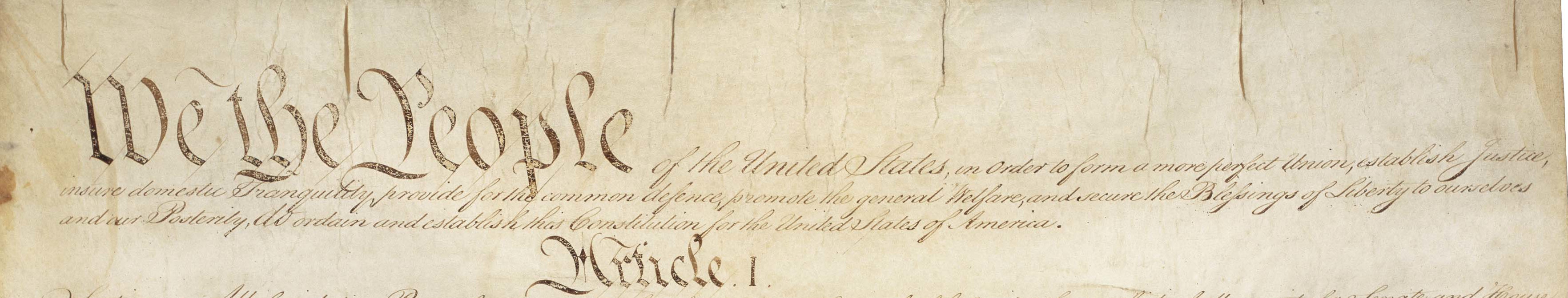

In 1764, to pay the war debt and fund the defense of the colonies, Parliament passed the American Revenue Act, also known as the Sugar Act. Up until 1764, the colonial assemblies had raised their own taxes; Parliament had regulated trade. When Parliament passed the Sugar Act, which chiefly required stricter enforcement of earlier measures, some colonists challenged it by arguing that, because the colonies had no representatives in Parliament, Parliament had no right to levy taxes on them.

Parliament’s next revenue act induced a still more strenuous response. A 1765 Stamp Act required placing government-issued paper stamps on all manner of printed paper, from bills of credit to playing cards. Stamps were required across the British Empire, and, by those standards, the tax levied in the colonies was cheap: colonists paid only two-thirds of what Britons paid. But in the credit-strained mainland colonies, this proved difficult to bear. Opponents of the act began styling themselves the Sons of Liberty (after the Sons of Liberty in 1750s Ireland) and describing themselves as rebelling against slavery.

In October, the month before the Stamp Act was to take effect, twenty-seven delegates from nine colonies met in a Stamp Act Congress in New York’s city hall

And yet this defiance did not extend to Quebec, or to the sugar islands, where the burden of the Stamp Tax was actually heavier. Thirteen colonies eventually cast off British rule; some thirteen more did not.

British planters in the West Indies barely uttered a complaint. (South Carolina, whose economy had more in common with the British West Indies than with the mainland colonies, wavered.) They were too worried about the possibility of inciting yet another slave rebellion.

On the mainland, whites outnumbered blacks, four to one. On the islands, blacks outnumbered whites, eight to one. One-quarter of all British troops in British America were stationed in the West Indies, where they protected English colonists from the ever-present threat of slave rebellion. For this protection, West Indian planters were more than willing to pay a tax on stamps. Planters in Jamaica were still reeling from the latest insurrection,

Unsurprisingly, the island planters’ unwillingness to join the protest against the Stamp Act greatly frustrated the Sons of Liberty.

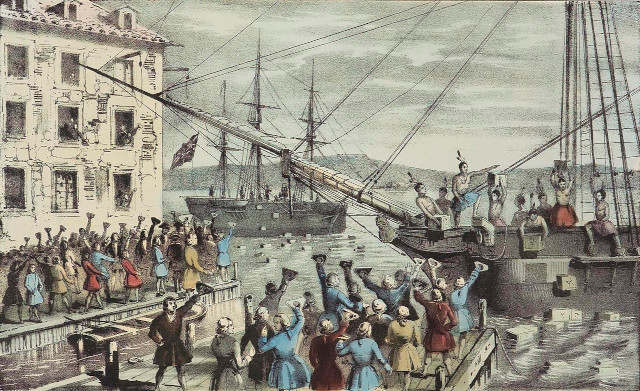

The London-based East India Company was at risk of bankruptcy, partly due to the colonial boycott, but more due to a famine in Bengal, the military costs it incurred there, and collapsing stock value consequent to the empire-wide credit crash of 1772. In May of 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, which reduced the tax on tea—as a way of saving the East India Company—but again asserted Parliament's right to tax the colonies. Townspeople in Philadelphia called anyone who imported the tea “an enemy of the country.” Tea agents resigned their posts in fear. That fall, three ships loaded with tea arrived in Boston. On the night of December 16, dozens of colonists disguised as Mohawks—warring Indians—boarded the boats and dumped chests of the tea into the harbor. To punish the city, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, which closed Boston Harbor and annulled the Massachusetts charter, effective in June of 1774.

Meanwhile, at Mount Vernon, George Washington, who'd been elected to the Virginia legislature in 1758, had chiefly occupied himself managing his considerable tobacco estate.

He hadn’t been much animated by the colonies’ growing resistance to parliamentary authority until the passage of the Coercive Acts. In September, fifty-six delegates from twelve of the thirteen mainland colonies met in Philadelphia, in a carpenters’ guildhall, as the First Continental Congress. Washington served as a delegate from Virginia. But if protest over the Stamp Act had temporarily united the colonies, the Coercive Acts appeared to many delegates to be merely Massachusetts’s problem. To Virginians, the delegates from Massachusetts seemed intemperate and rash, fanatical, even, especially when they suggested the possibility of an eventual independence from Britain. In October, Washington expressed relief when, after speaking to the “Boston people,” he felt confident that he could “announce it as a fact, that it is not the wish or interest of that Government, or any other upon this Continent,separately or collectively, to set up for Independency.” He was as sure “as I can be of my existence, that no such thing is desired by any thinking man in all North America.”

How would representation be calculated? Virginia delegate Patrick Henry, an irresistible orator with a blistering stare, suggested that the delegates cast a number of votes proportionate to their colonies’ number of white inhabitants. Given the absence of any accurate population figures, the delegates had little choice but to do something far simpler —to grant each colony one vote. In any case, the point of meeting was to become something more than a collection of colonies and the sum of their grievances: a new body politic. “The distinction between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders is no more,” Henry said. “I am not a Virginian, but an American.” A word on a long-ago map had swelled into an idea.