Between 1500 and 1800, roughly two and a half million Europeans moved to the Americas; they carried twelve million Africans there by force; and as many as fifty million Native Americans died, chiefly of disease. Europe is spread over about four million square miles, the Americas over about twenty million square miles. For centuries, geography had constrained Europe’s demographic and economic growth; that era came to a close when Europeans claimed lands five times the size of Europe. Taking possession of the Americas gave Europeans a surplus of land; it ended famine and led to four centuries of economic growth, growth without precedent, growth many Europeans understood as evidence of the grace of God. One Spaniard, writing from New Spain to his brother in Valladolid in 1592, told him, “This land is as good as ours, for God has given us more here than there, and we shall be better off.” Even the poor prospered.

The European extraction of the wealth of the Americas made possible the rise of capitalism: new forms of trade, investment, and profit. Between 1500 and 1600 alone, Europeans recorded carrying back to Europe from the Americas nearly two hundred tons of gold and sixteen thousand tons of silver; much more traveled as contraband. “The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind,” Adam Smith wrote, in The Wealth of Nations, in 1776. But the voyages of Columbus and Dias also marked a turning point in the development of another economic system, slavery: the wealth of the Americas flowed to Europe by the forced labor of Africans.

Slavery had been practiced in many parts of the world for centuries. People tended to enslave their enemies, people they considered different enough from themselves to condemn to lifelong servitude. Sometimes, though not often, the status of slaves was heritable: the children of slaves were condemned to a life of slavery, too. Many wars had to do with religion, and because many slaves were prisoners of war, slaves and their owners tended to be people of different faiths: Christians enslaved Jews; Muslims enslaved Christians; Christians enslaved Muslims. Since the Middle Ages, Muslim traders from North Africa had traded in Africans from below the Sahara, where slavery was widespread. In much of Africa, labor, not land, constituted the sole form of property recognized by law, a form of consolidating wealth and generating revenue, which meant that African states tended to be small and that, while European wars were fought for land, African wars were fought for labor. People captured in African wars were bought and sold in large markets by merchants and local officials and kings and, beginning in the 1450s, by Portuguese sea captains.

Columbus, a veteran of that trade, reported to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492 that it would be the work of a moment to enslave the people of Haiti, since “with 50 men all of them could be held in subjection and can be made to do whatever one might wish.” In sugar mines and gold mines, the Spanish worked their native slaves to death while many more died of disease. Soon, they turned to another source of forced labor, Africans traded by the Portuguese.

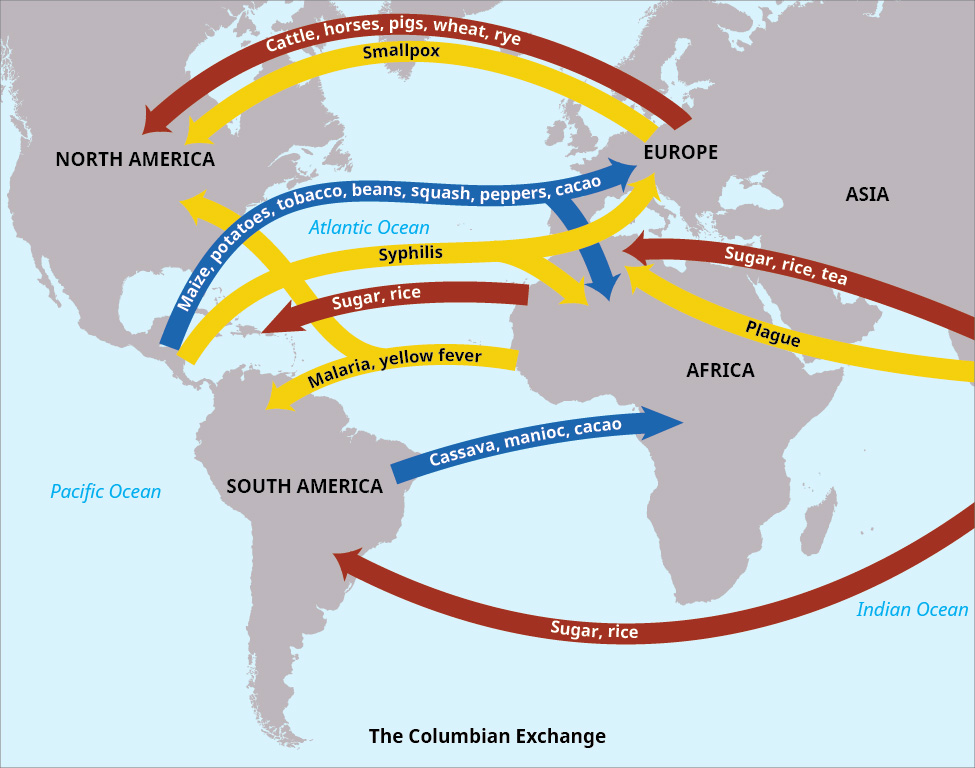

When Columbus made a second voyage across the ocean in 1493, he commanded a fleet of seventeen ships carrying twelve hundred men, and another kind of army, too: seeds and cuttings of wheat, chickpeas, melons, onions, radishes, greens, grapevines, and sugar cane, and horses, pigs, cattle, chickens, sheep, and goats, male and female, two by two. Hidden among the men and the plants and the animals were stowaways, seeds stuck to animal skins or clinging to the folds of cloaks and blankets, in clods of mud. Most of these were the seeds of plants Europeans considered to be weeds, like bluegrass, daisies, thistle, nettles, ferns, and dandelions. Weeds grow best in disturbed soil, and nothing disturbs soil better than an army of men, razing forests for timber and fuel and turning up the ground cover with their boots, and the hooves of their horses and oxen and cattle. Livestock eat grass; people eat livestock: livestock turn grass into food that humans can eat. The animals that Europeans brought to the New World—cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, chickens, and horses—had no natural predators in the Americas but they did have an abundant food supply. They reproduced in numbers unfathomable in Europe. Cattle populations doubled every fifteen months. Nothing, though, beat the pigs. Pigs convert one-fifth of everything they eat into food for human consumption (cattle, by contrast, convert one-twentieth); they feed themselves, by foraging, and they have litters of ten or more. Within a few years of Columbus’s second voyage, the eight pigs he brought with him had descendants numbering in the thousands. Wrote one observer, “All the mountains swarmed with them.”

Meanwhile, the people of the New World: They died by the hundreds. They died by the thousands, by the tens of thousands, by the hundreds of thousands, by the tens of millions. The isolation of the Americas from the rest of the world, for hundreds of millions of years, meant that diseases to which Europeans and Africans had built up immunities over millennia were entirely new to the native peoples of the Americas. European ships, with their fleets of people and animals and plants, brought along, unseen, battalions of diseases: smallpox, measles, diphtheria, trachoma, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, malaria, typhoid fever, yellow fever, dengue fever, scarlet fever, amoebic dysentery, and influenza, diseases that had evolved alongside humans and their domesticated animals living in dense, settled populations—cities—where human and animal waste breeds vermin, like mice and rats and roaches. Most of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, though, didn’t live in dense settlements, and even those who lived in villages tended to move with the seasons, taking apart their towns and rebuilding them somewhere else. They didn’t accumulate filth, and they didn’t live in crowds. They suffered from very few infectious diseases. Europeans, exposed to these diseases for thousands of years, had developed vigorous immune systems, and antibodies particular to bacteria to which no one in the New World had ever been exposed.

The consequence was catastrophe. Of one hundred people exposed to the smallpox virus for the first time, nearly one hundred became infected, and twenty-five to thirty-three died. Before they died, they exposed many more people: smallpox incubates for ten to fourteen days, which meant that people who didn’t yet feel sick tended to flee, carrying the disease as far as they could go before collapsing. Some people who were infected with smallpox could have recovered, if they’d been taken care of, but when one out of every three people was sick, and a lot of people ran, there was no one left to nurse the sick, who died of thirst and grief and of being alone. And they died, too, of torture: already weakened by disease, they were worked to death, and starved to death. On the islands in the Caribbean, so many natives died so quickly that Spaniards decided very early on to conquer more territory, partly to take more prisoners to work in their gold and silver mines, as slaves.

Spanish conquistadors first set foot on the North American mainland in 1513; in a matter of decades, New Spain spanned not only all of what became Mexico but also more than half of what became the continental United States, territory that stretched, east to west, from Florida to California, and as far north as Virginia on the Atlantic Ocean and Canada on the Pacific. Diseases spread ahead of the Spanish invaders, laying waste to wide swaths of the continent. It became commonplace, inevitable, even, first among the Spanish, and then, in turn, among the French, the Dutch, and the English, to see their own prosperity and good health and the terrible sicknesses suffered by the natives as signs from God. “Touching these savages, there is a thing that I cannot omit to remark to you,” one French settler wrote: “it appears visibly that God wishes that they yield their place to new peoples.” Death convinced them at once of their right and of the truth of their faith.

[See These Truths pg16-20]