From These Truths:

The Constitution drafted in Philadelphia acted as a check on the Revolution, a halt to its radicalism; if the Revolution had tilted the balance between government and liberty toward liberty, the Constitution shifted it toward government. But in very many ways the Constitution also realized the promise of the Revolution, and particularly the promise of representation. In devising the new national government, the delegates adamantly rejected a proposal that the state legislators, rather than the people, elect members of Congress. “Under the existing Confederacy, Congress represent the States not the people of the States,” George Mason said, “their acts operate on the States not on the individuals. The case will be changed in the new plan of Government. The people will be represented; they ought therefore to choose the Representatives.”

… (pg 121-2)

The most difficult question at the convention concerned representation. States with large populations of course wanted representation in the federal legislature to be proportionate to population. States with small populations wanted equal representation for each state. States with large numbers of slaves wanted slaves to count as people for purposes of representation but not for purposes of taxation; states without slaves wanted the opposite. “If .. . we depart from the principle of representation in proportion to numbers, we will lose the object of our meeting,” Pennsylvania’s James Wilson warned on June 9.4! That same day, or probably later that evening, Benjamin Franklin, catching up on his correspondence, distributed to notable antislavery leaders around the world copies of the new constitution of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, “for in this business the friends of humanity in every Country are of one Nation and Religion.”42 Franklin spoke at the convention on the question of representation, but it was Wilson, his fellow Pennsylvanian, who treated the matter squarely. Better than any other delegate, Wilson understood the nature of the political divide—a divide that would, in a matter of decades, sunder the Union.

On July 11, Wilson asked why, if slaves were admitted as people, they weren't “admitted as Citizens.” And “then why are they not admitted on an equality with White Citizens?” And, if they weren't admitted as people, “Are they admitted as property? Then why is not other property admitted into the computation?”

… (pg 124)

A compromise between those opposed to the slave trade and those in favor of it was reached with a motion that Congress should be prohibited from interfering with the slave trade for a period of twenty years. Madison was aggrieved. He’d have preferred no mention of slavery in the Constitution at all. “So long a term will be more dishonorable to the national character than to say nothing about it in the Constitution,” he warned. Gouverneur Morris, who'd lost a leg to a carriage wheel and the use

of an arm to a boiling pot of water, was appalled at the entire bargain, and decided to deliver a lecture. “The inhabitant of Georgia and S.C. who goes to the Coast of Africa, and in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity tears away his fellow creatures from their dearest connections & damns them to the most cruel bondages, shall have more votes in a Govt. instituted for protection of the rights of mankind, than the Citizen of Pa. or N. Jersey who views with a laudable horror, so nefarious a practice.” He said he “would sooner submit to a tax for paying for all the Negroes in the United States than saddle posterity with such a Constitution.” As Morris pointed out, the delegates were there to build a republic, but there was nothing more aristocratic than slavery. He called it “the curse of heaven.”

The Constitution would not lift that curse. Instead, it tried to hide it. Nowhere do the words “slave” or “slavery” appear in the final document. “What will be said of this new principle of founding a right to govern Freemen on a power derived from slaves,” Pennsylvania's John Dickinson wondered—correctly, as it would turn out. He predicted: “The omitting the Word will be regarded as an Endeavour to conceal a principle of which we are ashamed.”

… (pg 126-7)

Ratification proved to be a nail-biter. By January 9, 1788, five states—Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—had ratified. The debate that began in mid-January at the convention in Massachusetts grew heated. “You Perceive we have some quarilsome spirits against the constitution,” Jane Franklin reported to her brother from Massachusetts. “But,” she reassured him, “it does not appear to be those of Superior Judgment.” After Federalists promised they’d propose a bill of rights at the first session of the new Congress, Massachusetts, in a squeaker, voted in favor of ratification by a vote 187 to 168 in February. In March, Rhode Island, which had refused to send any delegates to the constitutional convention, refused to hold a ratifying convention. Maryland ratified in April, South Carolina in May, New Hampshire in June. That made nine states in favor, meeting the minimum required.

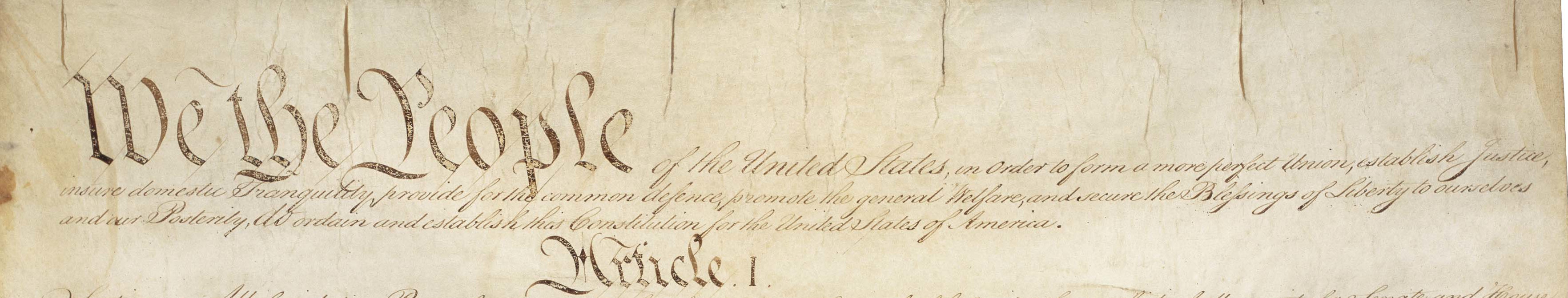

Practically, though, the approval of Virginia and New York was essential. At Virginia’s convention, Patrick Henry argued that the Constitution was an assault on the sovereignty of the states: “Have they made a proposal of a compact between states? If they had, this would be a confederation: It is otherwise most clearly a consolidated government. The question turns, sir, on that poor little thing—the expression, We, the people, instead of the states, of America.” But Federalists eventually prevailed, by a vote of 89 to 79, on June 25, 1788.

On the Fourth of July, James Wilson, with full-throated passion, spoke at a parade in Philadelphia, while a ratifying convention met in New York. “You have heard of Sparta, of Athens, and of Rome; you have heard of their admired constitutions, and of their high-prized freedom,” he told his audience. Then he asked a series of rhetorical questions. But were their constitutions written? The crowd called back, “No!” Were they written by the people? No! Were they submitted to the people for ratification? No! “Were they to stand or fall by the people's approving or rejecting vote?” No, again.

Three weeks later, New York ratified by the smallest of margins: 30 to 27. By three votes, the Constitution became law. And yet the political battle raged on. The day after the vote, Thomas Greenleaf, the only Anti-Federalist printer in Federalist-dominated New York City, arrived home in the evening to find that a band of Federalists had fired musket balls into his house. He loaded two pistols, put them in a chest near his bed, and went to sleep, only to be awakened in the middle of the night by men shouting outside his house. When a mob began breaking down his door, smashing windows, and throwing stones, Greenleaf shot into the crowd from a second-story window, tried to reload, then decided to run. After he and his wife and children made a narrow escape out the back door, the mob swarmed his house and office and destroyed his type and printing press, a bad omen for a nation founded on the freedom of speech.

Ratification had been an agony. It might very easily have gone another way. An unruly new republic had begun.

(pg 130-1)